The University of California (UC) has fired another legal salvo in the prolonged patent battle over CRISPR, the revolutionary gene-editing technology that has spawned a billion-dollar industry.

UC leads a group of litigants who contend that the U.S. Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) wrongly sided with the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and two partners—Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge—in February when it ruled that the Broad group invented the use of CRISPR in eukaryotic cells. After that ruling, UC moved the battleground to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. In a 25 July brief to the Federal Circuit, the UC group contends that PTAB “ignored key evidence” and “made multiple errors.”

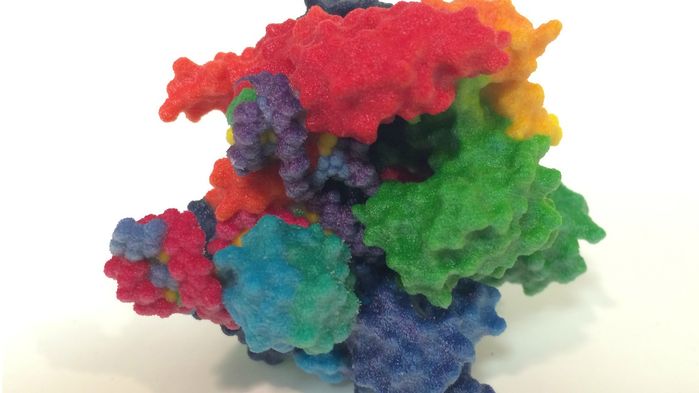

The CRISPR battle

The UC litigants indisputably first showed in 2012 that CRISPR could work in DNA of simpler organisms, and soon after filed a patent application on the gene-editing technique. They claim the Broad group learned from that disclosed invention and applied CRISPR to eukaryotic cells. The essential legal question is whether the Broad’s patent application is a novel, patentable invention, or whether it was “obvious” in the sense that “anyone skilled in the art”—in other words, any trained molecular biologist—would have a “reasonable expectation of success” of using the CRISPR system to edit genes in eukaryotic cells.

The UC group contends PTAB ignored key decisions on these general questions made by the U.S. Supreme Court and the Federal Circuit. It reiterated its long-held claim that applying CRISPR to eukaryotic cells was so obvious that six different labs did it in the same time frame, which it complains the PTAB “essentially dismissed as ‘irrelevant.’” And its brief notes that patent examiners rejected similar eukaryotic cell CRISPR patent applications from Sigma-Aldrich and ToolGen—filed before the Broad’s patent application—because it made claims that were “non-novel” or obvious in light of UC’s disclosed work.

Jacob Sherkow, an intellectual property attorney at the New York Law School in New York City who has closely followed each round in the fierce battle, says the UC group’s brief at times “overplays these mistakes relative to the PTAB’s analysis.” He notes that the PTAB’s decision was “thorough” and the standards to overturn its decisions are high. “While there were some interesting chestnuts in its brief—such as UC pointing out that the PTAB virtually ignored some important patents pending at the time [the Broad] patent was filed—I don’t think that’s going to be enough to win the day [for] UC,” he says.

In a statement, the Broad Institute suggested the UC will not prevail in its challenge:

Notably, the [UC] brief hinges on its argument that, although [UC]’s work simply involved characterizing a purified enzyme in a test tube, it rendered obvious that genome editing could be made to work in living mammalian cells.

This is inaccurate, as the PTAB noted repeatedly in its decision.

Updated, 7/26/2017, 12:33 p.m.: Statement from the Broad Institute added.