SEATTLE, WASHINGTON—Positive results from small clinical studies without control groups often get dismissed as anecdote, and for good reason: Many don’t pan out in more rigorous trials. But when a field suffers as much failure as the search for an AIDS vaccine has over the past 30 years, researchers sometimes celebrate glimpses of hope.

That’s what happened here last week when scientists showed that a vaccine may have helped five people already infected with HIV keep the virus in check—a “functional cure” as some call it. The results, which need to be confirmed in larger studies, suggest the vaccine may boost the immune system enough to allow infected people to drive down HIV levels without taking drugs—although it’s not clear for how long.

“It’s the proof of concept that through therapeutic vaccination we can really re-educate our T cells to control the virus,” says Beatriz Mothe, a clinician at IrsiCaixa AIDS Research Institute in Barcelona, Spain, who presented the results here at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. “This is the first time that we see this is possible in humans.”

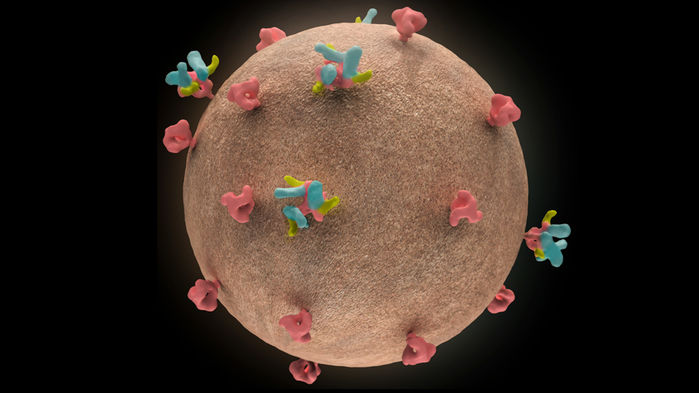

Despite intensive efforts and massive investments, no vaccine to prevent HIV infection has yet proved itself and come to market. Researchers have also tested so-called therapeutic vaccines, which aim to help infected people keep the virus at bay for months or even years without antiretroviral (ARV) drugs. Mothe and her colleagues tried that strategy with an HIV vaccine made by Tomáš Hanke of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.

The 13 participants in the study had taken ARVs on average for 3.2 years; all had started treatment within 6 months after becoming infected, which helped keep HIV in their blood down to undetectable levels on standard tests. (More sensitive tests used solely for research purposes can detect HIV in all infected people.) The researchers theorized this had limited HIV’s ability to integrate into their chromosomes, leaving them with relatively small “reservoirs” of infected cells. This, in turn, should make it easier for them to contain the virus if ARVs are stopped—especially with a helping hand from a vaccine.

After receiving a series of three shots of the vaccine, the participants stopped taking ARVs. Within 4 weeks, the virus came roaring back in eight of them. The other five, however, have now gone between 6 and 28 weeks without having to restart treatment. Each of these “controllers” has had the virus become temporarily detectable at some point, but these “blips” have never gone above 2000 copies per milliliter on two occasions—the study’s criterion for restarting ARVs.

Of more than 50 therapeutic vaccine trials so far, this is the first one that has bolstered the immune system in a “meaningful” way, says Steven Deeks, an HIV/AIDS clinician and researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who is “cautiously optimistic” that the data will inspire others to study the approach.

The evidence did not bowl over immunologist Daniel Douek of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland, however. “The results are encouraging, but it is difficult to gauge what the effect of the procedure actually was because of the uncontrolled nature of the study and the fact that the people who remain off [ARVs] are, nevertheless, viremic,” Douek says.

But Mothe stresses that previous “treatment interruption studies” in people who started ARVs soon after becoming infected have found that only 10% control their infections for longer than 4 weeks. In this case, 38% of the participants passed that milestone. Deeks agrees. “Should the current trends persist, it is hard to argue that the vaccine strategy did not do something, but controlled studies are needed,” he says.

HIV notoriously dodges immune attack—and preventive vaccination—by mutating. Deeks and others believe the trial may have been partly successful because the vaccine contains HIV genes that code for “highly conserved” internal structures and enzymes that cannot change much without harming the virus. Before the vaccination, only 4% of the participants’ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell that helps control infections) specifically targeted these conserved proteins; after vaccination, that jumped to 67%.

“I’m pretty excited about this,” says Sharon Lewin, who heads the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia. “But there are lots of questions.” Mothe and colleagues hope to answer them by continuing to monitor their participants and staging a larger, more rigorous trial of the concept soon.